Search

Search results

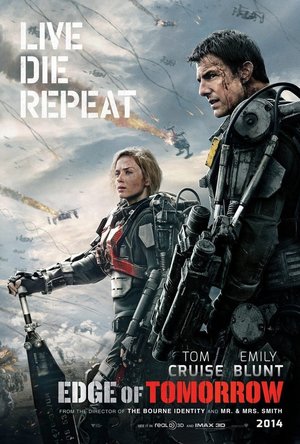

5 Minute Movie Guy (379 KP) rated Live Die Repeat: Edge of Tomorrow (2014) in Movies

Jun 26, 2019

One of the best action films of Tom Cruise's incredible career. (4 more)

Emily Blunt is a true force to be reckoned with.

The film's aliens and special effects are simply outstanding.

Unexpectedly hilarious. Who knew watching Tom Cruise die repeatedly could be so funny?

Edge of Tomorrow feels like a video game made into an unforgettably great movie.

Edge of Tomorrow is one of the best action movies of Tom Cruise’s illustrious career and might just be the most fun you'll have at the movies all year.

Amidst the yearly barrage of unimaginative action movies, Edge of Tomorrow is a breath of fresh air. It’s smart, funny, and full of action-packed excitement. It is a definitive summer blockbuster and is one of the best action movies of Tom Cruise’s illustrious career. Based on the graphic novel All You Need is Kill by Hiroshi Sakurazaka, Edge of Tomorrow stars Tom Cruise as Major William Cage, who has earned his rank without ever having served a day in combat. All of that quickly comes to a change when he’s put on the frontlines of a war that threatens humanity’s entire existence. Thrust into combat, Cage is cowardly, and also comically unprepared. He fearfully fights for his life, but is quickly killed in the conflict, only to reawaken at the start of the same day. Cage is given another chance at life, with the benefit of having lived the day before and fully remembering it. This is not a gift bestowed upon Tom Cruise by the power of Scientology, nor by Tom Cruise’s near-invincibility in his films, but instead his character Cage inadvertently has tapped into a divine alien power through which he is able to re-spawn from death over and over again. Trapped In this seemingly infinite loop, Cage is able to learn from his mistakes and thereby has the power to single-handedly change the outcome of this war and save the human race from complete annihilation.

The brilliance of Edge of Tomorrow is in its execution. This is a movie that could have easily been tiresome considering it replays the same day continuously on repeat, but it’s handled in a way that makes it entertaining and engaging. It is superbly edited to keep the story moving and the laughs coming. Even as a huge fan of Tom Cruise, I had a marvelous time watching him die off again and again while thoroughly laughing at his expense. What makes it so funny is that Tom is completely in on the joke and is able to generously poke fun at himself. He is perfectly cast in this role, as it allows him to act totally crazy and completely spineless, while gradually transitioning into his usual kick-ass, cool Cruise persona. Edge of Tomorrow feels both exhilarating and original, although it is clearly inspired in part by some other films, such as the comedy classic Groundhog Day, and even The Matrix trilogy. However, having these influences doesn’t take away from the film’s enormous accomplishments. To call it an action sci-fi version of Groundhog Day is only to sell it short. In fact, Edge of Tomorrow might just be the most fun you’ll have at the movies all year.

The conflict in Edge of Tomorrow is an alien invasion that is obliterating humanity. The aliens, known as Mimics, have taken over most of Europe, and with the exception of one keystone battle, have easily routed human military forces. Rita Vrataski, played by Emily Blunt, led that decisive victory at Verdun, earning herself the moniker the “Angel of Verdun” after single-handedly killing hundreds of Mimics in humanity’s first and only victory against the alien species. How was one woman able to massacre these aliens that can lay waste to an armed infantry in minutes? Well, as Cage finds out, she previously had his ability to reset in death, although she no longer possesses that power. Nevertheless, with her knowledge and skill set acquired from her nearly infinite practice, she can transform Cage into Earth’s greatest weapon.

Edge of Tomorrow is a thoroughly impressive package, complete with superb special effects, a heart-pounding musical score, and outstanding performances from its lead characters. Tom Cruise carries the film with veteran expertise, making the film fun and deeply entertaining. Emily Blunt is a powerhouse as Rita, showcasing a heroic toughness with a survivor mentality. I don’t think there are many actresses in Hollywood that could play such a role as convincingly as Blunt does here. Meanwhile, Bill Paxton is as enjoyable to watch as ever. He plays Master Sergeant Farrell, who is Cage’s cocky commanding officer that takes great pleasure in giving him a hard time. As for the aliens in the movie, they look absolutely incredible, not to mention highly original. I think they’re some of the coolest aliens I’ve ever seen, and they’re also far more threatening than your typical movie alien. They’re deathly fast and unpredictable, which makes the film’s action all the more intense. Edge of Tomorrow actually feels very much like a video game, and not just because of the respawning feature. The characters are memorable, the stakes are high, and the action is so engrossing that you feel like you’re an active participant in it. The creativity and combat at work in this film are worthy of belonging in a blockbuster game series. It rarely lets up and is an adrenaline-fueled ride from beginning to end.

I’ll admit that Edge of Tomorrow far-exceeded my expectations. It’s cool in every way imaginable, from the story and the action to the aliens and characters. It will immerse you in its desolate, doomed world that unknowingly rests on the brink of total destruction. Tom Cruise and Emily Blunt are both in top form and make this a movie you won’t want to miss. Edge of Tomorrow is certain to become an instant action classic. One that I wholly look forward to watching again and again and again.

(This review was originally posted at 5mmg.com on 6.30.14.)

The brilliance of Edge of Tomorrow is in its execution. This is a movie that could have easily been tiresome considering it replays the same day continuously on repeat, but it’s handled in a way that makes it entertaining and engaging. It is superbly edited to keep the story moving and the laughs coming. Even as a huge fan of Tom Cruise, I had a marvelous time watching him die off again and again while thoroughly laughing at his expense. What makes it so funny is that Tom is completely in on the joke and is able to generously poke fun at himself. He is perfectly cast in this role, as it allows him to act totally crazy and completely spineless, while gradually transitioning into his usual kick-ass, cool Cruise persona. Edge of Tomorrow feels both exhilarating and original, although it is clearly inspired in part by some other films, such as the comedy classic Groundhog Day, and even The Matrix trilogy. However, having these influences doesn’t take away from the film’s enormous accomplishments. To call it an action sci-fi version of Groundhog Day is only to sell it short. In fact, Edge of Tomorrow might just be the most fun you’ll have at the movies all year.

The conflict in Edge of Tomorrow is an alien invasion that is obliterating humanity. The aliens, known as Mimics, have taken over most of Europe, and with the exception of one keystone battle, have easily routed human military forces. Rita Vrataski, played by Emily Blunt, led that decisive victory at Verdun, earning herself the moniker the “Angel of Verdun” after single-handedly killing hundreds of Mimics in humanity’s first and only victory against the alien species. How was one woman able to massacre these aliens that can lay waste to an armed infantry in minutes? Well, as Cage finds out, she previously had his ability to reset in death, although she no longer possesses that power. Nevertheless, with her knowledge and skill set acquired from her nearly infinite practice, she can transform Cage into Earth’s greatest weapon.

Edge of Tomorrow is a thoroughly impressive package, complete with superb special effects, a heart-pounding musical score, and outstanding performances from its lead characters. Tom Cruise carries the film with veteran expertise, making the film fun and deeply entertaining. Emily Blunt is a powerhouse as Rita, showcasing a heroic toughness with a survivor mentality. I don’t think there are many actresses in Hollywood that could play such a role as convincingly as Blunt does here. Meanwhile, Bill Paxton is as enjoyable to watch as ever. He plays Master Sergeant Farrell, who is Cage’s cocky commanding officer that takes great pleasure in giving him a hard time. As for the aliens in the movie, they look absolutely incredible, not to mention highly original. I think they’re some of the coolest aliens I’ve ever seen, and they’re also far more threatening than your typical movie alien. They’re deathly fast and unpredictable, which makes the film’s action all the more intense. Edge of Tomorrow actually feels very much like a video game, and not just because of the respawning feature. The characters are memorable, the stakes are high, and the action is so engrossing that you feel like you’re an active participant in it. The creativity and combat at work in this film are worthy of belonging in a blockbuster game series. It rarely lets up and is an adrenaline-fueled ride from beginning to end.

I’ll admit that Edge of Tomorrow far-exceeded my expectations. It’s cool in every way imaginable, from the story and the action to the aliens and characters. It will immerse you in its desolate, doomed world that unknowingly rests on the brink of total destruction. Tom Cruise and Emily Blunt are both in top form and make this a movie you won’t want to miss. Edge of Tomorrow is certain to become an instant action classic. One that I wholly look forward to watching again and again and again.

(This review was originally posted at 5mmg.com on 6.30.14.)

Daniel Boyd (1066 KP) rated GoodFellas (1990) in Movies

Aug 25, 2020

Cast (3 more)

Sets

Script

Directing

Masterpiece

Contains spoilers, click to show

At the weekend, I was lucky enough to go and see one of my favourite films ever made on the big screen; Goodfellas. I thoroughly enjoyed the experience of seeing the movie in an actual cinema, but it has been a few years since I have last seen it and seeing it after seeing some of Scorsese’s more recent efforts, I actually saw the story in a different light.

Here me out here; Goodfellas is a religious story.

I know what you are thinking, “But Scorsese has already made religious movies with The Last Temptation of Christ and Silence. Goodfellas is about gangsters and murder and the only brief mention of religion in the movie is the fact that Karen is Jewish and Henry wears a cross.” Well none of that is strictly untrue, but there were just several points of the movie that I just couldn’t help but feel an implied religious undertone.

The first of which is in the opening scene of the movie, when Henry, Tommy and Jimmy open the boot of the car to finish off Billy Batts. The bright red tail light shines harshly on Henry’s face as he watches a man die and delivers his iconic voiceover: “As far back as I can remember, I’ve always wanted to be a gangster.” Here we are being introduced to a man who is capable of literally staring death in the face and metaphorically staring into the jaws of hell without even flinching.

From this point on, Henry is our guide into this forbidden underworld. He treats us the viewers as total newcomers to this chaotic landscape as he attempts to sell to us how great it is to live this way. It’s akin to Virgil guiding Dante through the various circles of hell in the Divine Comedy. This idea of Henry being a guide into hell is most explicit in the scene of his and Karen’s first real date at the Copacabana nightclub. In this scene we are treated to a glorious tracking shot that follows the couple all the way from their car to their seat directly in front of the stage. The first major direction we are taken is down. We descend down a staircase into a hallway painted red, in fact if you pay attention to the background in this entire sequence, there is almost always at least one red object onscreen. All the way to the table, Henry is greeted by various sinners as the ‘Then He Kissed Me,’ plays in the background; a song of seduction and lust.

Another example of this is the famous scene where Henry introduces us to various gangsters such as Jimmy Two Times through voiceover. Once again, the environment is littered with red light and dark shadowed areas as we are being introduced to a batch of sinners, thieves and murderers.

After Tommy’s death, the period of seduction in the movie is over. From this point on, we are seeing the intense fall of Henry’s world. It is just as chaotic as the first half of the movie, but now Henry and his friends are no longer in charge of the chaos and slowly they are beginning to lose control of everything that was once theirs. All of a sudden the momentum that has carried the movie and Henry’s life up until this point is brought to a halt, most obviously manifested in the scene of Henry driving far too fast despite being unaware of wait awaits him ahead and having to slam on his breaks and come to a screeching stop mere inches away from crashing. What direction is he looking just prior to this? He’s looking up for the chopper that he suspects has been following him, however he is also looking in the direction of Heaven, looking for a threat of something bigger than him that threatens to put a stop to his sinful lifestyle.

In the movie’s epilogue, once Henry gives up Jimmy and Paulie to the FBI, we see him in an entirely different environment. He’s dressed different, the weather is different and he describes how he is now just a nobody like everyone else as if that to him is a fate worse that death. Almost as if, he is in Limbo. No longer is he amongst the sinners in a world of gratification and sin, but instead he is in a ‘safe,’ environment where he can’t do anything even remotely illegal or morally questionable because he is being monitored by people just waiting for him to slip up. Then the very last shot we see is Tommy shooting at the audience. This is not only a very neat bookend as both the opening scene and final scene of the movie see Tommy committing a violent act, but it signifies that elements of Henry’s old life still follow him and he will spend the rest of his days looking over his shoulder for demons from his old life, like Tommy waiting to snuff him out.

Maybe I’m reaching slightly with this, but I feel like at least a few of these choices were intentionally put in by Scorsese. Especially the opening scene showing the murder of Billy Batts and the tracking shot as we are taken into the Copacabana. After watching recently watching Silence and The Irishman, it is clear that faith and mortality are both things that heavily weigh on Scorsese’s mind, so I don’t think that it is too much of a stretch to say that it was probably something that was at least in the back of his mind in 1990.

Regardless, this movie is a masterpiece and is still great no matter how many times you have seen it previously. It feels so authentic and genuine through the direction and presentation and the fantastic performances given by the respective cast members allow the characters to feel so real and deep. There is a reason that this is still considered as one of the seminal gangster movies. 10/10

Here me out here; Goodfellas is a religious story.

I know what you are thinking, “But Scorsese has already made religious movies with The Last Temptation of Christ and Silence. Goodfellas is about gangsters and murder and the only brief mention of religion in the movie is the fact that Karen is Jewish and Henry wears a cross.” Well none of that is strictly untrue, but there were just several points of the movie that I just couldn’t help but feel an implied religious undertone.

The first of which is in the opening scene of the movie, when Henry, Tommy and Jimmy open the boot of the car to finish off Billy Batts. The bright red tail light shines harshly on Henry’s face as he watches a man die and delivers his iconic voiceover: “As far back as I can remember, I’ve always wanted to be a gangster.” Here we are being introduced to a man who is capable of literally staring death in the face and metaphorically staring into the jaws of hell without even flinching.

From this point on, Henry is our guide into this forbidden underworld. He treats us the viewers as total newcomers to this chaotic landscape as he attempts to sell to us how great it is to live this way. It’s akin to Virgil guiding Dante through the various circles of hell in the Divine Comedy. This idea of Henry being a guide into hell is most explicit in the scene of his and Karen’s first real date at the Copacabana nightclub. In this scene we are treated to a glorious tracking shot that follows the couple all the way from their car to their seat directly in front of the stage. The first major direction we are taken is down. We descend down a staircase into a hallway painted red, in fact if you pay attention to the background in this entire sequence, there is almost always at least one red object onscreen. All the way to the table, Henry is greeted by various sinners as the ‘Then He Kissed Me,’ plays in the background; a song of seduction and lust.

Another example of this is the famous scene where Henry introduces us to various gangsters such as Jimmy Two Times through voiceover. Once again, the environment is littered with red light and dark shadowed areas as we are being introduced to a batch of sinners, thieves and murderers.

After Tommy’s death, the period of seduction in the movie is over. From this point on, we are seeing the intense fall of Henry’s world. It is just as chaotic as the first half of the movie, but now Henry and his friends are no longer in charge of the chaos and slowly they are beginning to lose control of everything that was once theirs. All of a sudden the momentum that has carried the movie and Henry’s life up until this point is brought to a halt, most obviously manifested in the scene of Henry driving far too fast despite being unaware of wait awaits him ahead and having to slam on his breaks and come to a screeching stop mere inches away from crashing. What direction is he looking just prior to this? He’s looking up for the chopper that he suspects has been following him, however he is also looking in the direction of Heaven, looking for a threat of something bigger than him that threatens to put a stop to his sinful lifestyle.

In the movie’s epilogue, once Henry gives up Jimmy and Paulie to the FBI, we see him in an entirely different environment. He’s dressed different, the weather is different and he describes how he is now just a nobody like everyone else as if that to him is a fate worse that death. Almost as if, he is in Limbo. No longer is he amongst the sinners in a world of gratification and sin, but instead he is in a ‘safe,’ environment where he can’t do anything even remotely illegal or morally questionable because he is being monitored by people just waiting for him to slip up. Then the very last shot we see is Tommy shooting at the audience. This is not only a very neat bookend as both the opening scene and final scene of the movie see Tommy committing a violent act, but it signifies that elements of Henry’s old life still follow him and he will spend the rest of his days looking over his shoulder for demons from his old life, like Tommy waiting to snuff him out.

Maybe I’m reaching slightly with this, but I feel like at least a few of these choices were intentionally put in by Scorsese. Especially the opening scene showing the murder of Billy Batts and the tracking shot as we are taken into the Copacabana. After watching recently watching Silence and The Irishman, it is clear that faith and mortality are both things that heavily weigh on Scorsese’s mind, so I don’t think that it is too much of a stretch to say that it was probably something that was at least in the back of his mind in 1990.

Regardless, this movie is a masterpiece and is still great no matter how many times you have seen it previously. It feels so authentic and genuine through the direction and presentation and the fantastic performances given by the respective cast members allow the characters to feel so real and deep. There is a reason that this is still considered as one of the seminal gangster movies. 10/10

Mandy and G.D. Burkhead (26 KP) rated Kushiel's Dart (Phèdre's Trilogy, #1) in Books

May 20, 2018

Shelf Life – Kushiel’s Legacy, the Naamah Trilogy, and How Jacqueline Carey Ruined My Ability to Be Impartial About Them

Contains spoilers, click to show

I can honestly say that the nine books that comprise these three trilogies are among the best fantasy available today as well as nine of my all-time favorite books I’ve ever read.

The Spoiler-Free Overview

If you want the shorter, less spoilery answer for what I think of these books: holy crap, yes, they’re as good as everyone says they are. Jacqueline Carey has a way of making me just…feel stuff like no other author can. Plenty of books have caught and held my interest enough that I didn’t want to put them down, but few have made the act of putting them down anyway so torturous. More than once, I hit a point in these stories where I had to drop whatever else I was gonna do that day (that I could realistically drop) just because I had to keep reading to make sure the characters were going to be okay.

This is character-driven fiction at its finest, with people in the pages who come alive and subtly win your heart. More than once, I’ve found reading about their ordeals to be worrying, a little bit painful, and a little bit infuriating (all in a good way, though), and I had to stop and remind myself that these weren’t real people that I was so concerned over and angry for. So if you ever wanted to be really, really invested in the story you’re reading and the people in it, Terre d’Ange is the place to go. All of the eroticism that everyone talks about is just a really nice bonus.

If you want an even shorter answer: do you watch Game of Thrones? Have you read George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire books? Have you at least heard of the fan hype around these stories? The Kushiel and Naamah books are like that, except sexier and with deeper court intrigue. And a lot less incest.

If you want the long answer…

A Dizzying Amount of Adventure Mileage

One thing that has to be said for Kushiel’s Legacy and the Naamah trilogy is that you definitely get your money’s worth of story out of each book. There’s a pattern that I’ve noticed with each of them, which is that you’ll follow the heroine/hero through a massive tribulation, see them endure their hardships and take their small victories where they can, then finally watch matters come to a crux, a climax, and a satisfying resolution…only to realize that you’re only a third of the way through the full page count.

Where most books are content to have one major conflict, Carey packs hers with about three each. The best part is that they’re not laid out in rigid sequence like a series of video game side quests – fight this problem, win, check it off the list, leave it behind and find a new one to fill the word count. No, each new adventure in the same book arises completely organically from the story overall. It makes you realize just how huge a scope these characters’ destinies really are, and just how incredibly wearying it can be and how much seemingly inhuman endurance it takes to be one of the gods’ chosen.

For instance, the first book to kick everything off, Kushiel’s Dart, begins slowly and simply enough. Phedre is an unwanted child who is basically sold into indentured servitude, then trained to be a spy and courtesan while we’re introduced to Terre d’Ange through her eyes over the next couple hundred pages, learning more about the politics and the players in time to watch the drama around them steadily unfold and escalate.

And then her wise mentor gets killed (as wise mentors tend to do), she and her bodyguard companion are betrayed, and the both of them get sold into full-on slavery to the vikings of Skaldia. Plenty of conflict and hardship and planning later, they make their escape and flee into harsh, snowy mountain terrain, falling in love for good measure while they fend off the deadly cold and the pursuit from their enemies. Finally, they make it back to their homeland and clear their names.

This is where most books would be content to stop and maybe leave further contentions for a sequel. Kushiel’s Dart would have been well within its rights to do so as well, and I wouldn’t have complained if it did. But no, it reminds readers, we’re not done yet. There’s a war coming, remember? We talked about this. Catch your breath for a moment, but then we gotta go rally our armies.

So Phedre and Joscelin set off to the wild and secluded island nation of Alba on the other side of an enchanted strait, a body of water where a vengeful, divine power known as the Master of the Straits lives and for some reason prevents almost all contact between the two nations. Arriving safely enough, they find that Alba is also war-torn at the moment, and the armies they had hoped to rally are busy defending their land from another foe. More plotting and intrigue ensues, alliances and promises are made, and with our heroes’ help, the two sides clash in a decisive battle that gains the side we’re rooting for victory as well as gives them their rightful sovereignty back. Now Phedre has the army she needs. After a sudden and unexpected stop at the Master of the Straits’ island, where they learn the secret of his power and guarantee indefinite safe passage between the nations in return for Phedre losing her closest friend, our heroes finally make it back to their homeland again with their army in tow.

Finally! After all of that struggle, we get a happy ending after all. But wait, not yet you don’t, the chunk of pages left at the end remind you. All you did was get your forces together. Good for you. Now you still gotta go actually fight the war with the Skaldi invaders to determine the fate of your entire nation.

So they do. And only after an awesome last-stand battle (the excitement and careful strategy of which will take you completely by surprise if you first entered this book expecting little more than kinky sex scenes) is the story allowed to wrap up in earnest, our heroes finally earning their long-deserved rest. The dangerous and cunning warlord is defeated, the invading army has been pushed back, the new Queen has ascended the throne, Terre d’Ange has been saved, and Phedre and Joscelin are free to finally be together – with the only little niggle being that the real mastermind behind all of their problems is still loose and taunting them. But we can get to that in the next book. Or five.

The Spoiler-Free Overview

If you want the shorter, less spoilery answer for what I think of these books: holy crap, yes, they’re as good as everyone says they are. Jacqueline Carey has a way of making me just…feel stuff like no other author can. Plenty of books have caught and held my interest enough that I didn’t want to put them down, but few have made the act of putting them down anyway so torturous. More than once, I hit a point in these stories where I had to drop whatever else I was gonna do that day (that I could realistically drop) just because I had to keep reading to make sure the characters were going to be okay.

This is character-driven fiction at its finest, with people in the pages who come alive and subtly win your heart. More than once, I’ve found reading about their ordeals to be worrying, a little bit painful, and a little bit infuriating (all in a good way, though), and I had to stop and remind myself that these weren’t real people that I was so concerned over and angry for. So if you ever wanted to be really, really invested in the story you’re reading and the people in it, Terre d’Ange is the place to go. All of the eroticism that everyone talks about is just a really nice bonus.

If you want an even shorter answer: do you watch Game of Thrones? Have you read George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire books? Have you at least heard of the fan hype around these stories? The Kushiel and Naamah books are like that, except sexier and with deeper court intrigue. And a lot less incest.

If you want the long answer…

A Dizzying Amount of Adventure Mileage

One thing that has to be said for Kushiel’s Legacy and the Naamah trilogy is that you definitely get your money’s worth of story out of each book. There’s a pattern that I’ve noticed with each of them, which is that you’ll follow the heroine/hero through a massive tribulation, see them endure their hardships and take their small victories where they can, then finally watch matters come to a crux, a climax, and a satisfying resolution…only to realize that you’re only a third of the way through the full page count.

Where most books are content to have one major conflict, Carey packs hers with about three each. The best part is that they’re not laid out in rigid sequence like a series of video game side quests – fight this problem, win, check it off the list, leave it behind and find a new one to fill the word count. No, each new adventure in the same book arises completely organically from the story overall. It makes you realize just how huge a scope these characters’ destinies really are, and just how incredibly wearying it can be and how much seemingly inhuman endurance it takes to be one of the gods’ chosen.

For instance, the first book to kick everything off, Kushiel’s Dart, begins slowly and simply enough. Phedre is an unwanted child who is basically sold into indentured servitude, then trained to be a spy and courtesan while we’re introduced to Terre d’Ange through her eyes over the next couple hundred pages, learning more about the politics and the players in time to watch the drama around them steadily unfold and escalate.

And then her wise mentor gets killed (as wise mentors tend to do), she and her bodyguard companion are betrayed, and the both of them get sold into full-on slavery to the vikings of Skaldia. Plenty of conflict and hardship and planning later, they make their escape and flee into harsh, snowy mountain terrain, falling in love for good measure while they fend off the deadly cold and the pursuit from their enemies. Finally, they make it back to their homeland and clear their names.

This is where most books would be content to stop and maybe leave further contentions for a sequel. Kushiel’s Dart would have been well within its rights to do so as well, and I wouldn’t have complained if it did. But no, it reminds readers, we’re not done yet. There’s a war coming, remember? We talked about this. Catch your breath for a moment, but then we gotta go rally our armies.

So Phedre and Joscelin set off to the wild and secluded island nation of Alba on the other side of an enchanted strait, a body of water where a vengeful, divine power known as the Master of the Straits lives and for some reason prevents almost all contact between the two nations. Arriving safely enough, they find that Alba is also war-torn at the moment, and the armies they had hoped to rally are busy defending their land from another foe. More plotting and intrigue ensues, alliances and promises are made, and with our heroes’ help, the two sides clash in a decisive battle that gains the side we’re rooting for victory as well as gives them their rightful sovereignty back. Now Phedre has the army she needs. After a sudden and unexpected stop at the Master of the Straits’ island, where they learn the secret of his power and guarantee indefinite safe passage between the nations in return for Phedre losing her closest friend, our heroes finally make it back to their homeland again with their army in tow.

Finally! After all of that struggle, we get a happy ending after all. But wait, not yet you don’t, the chunk of pages left at the end remind you. All you did was get your forces together. Good for you. Now you still gotta go actually fight the war with the Skaldi invaders to determine the fate of your entire nation.

So they do. And only after an awesome last-stand battle (the excitement and careful strategy of which will take you completely by surprise if you first entered this book expecting little more than kinky sex scenes) is the story allowed to wrap up in earnest, our heroes finally earning their long-deserved rest. The dangerous and cunning warlord is defeated, the invading army has been pushed back, the new Queen has ascended the throne, Terre d’Ange has been saved, and Phedre and Joscelin are free to finally be together – with the only little niggle being that the real mastermind behind all of their problems is still loose and taunting them. But we can get to that in the next book. Or five.

Mandy and G.D. Burkhead (26 KP) rated The Book of Kings in Books

May 20, 2018

Shelf Life – The Book of Kings Has a Few Gems and a Few Warts

Contains spoilers, click to show

Unlike other short story anthologies I could mention, this one wasn’t mostly horrible. Instead, the stories inside run the gamut from stupid to brilliant and from annoying to nothing special to fun and memorable. A little something for everyone, then.

So since I can’t review it with one blanket sentiment, let’s instead take a quick look at a handful of the 20 all-original stories inside. The following are the tales that most stood out to me during my reading, for better or worse.

“The Kiss” by Alan Dean Foster – A woman walking through a snowy city finds a frog who says he’s a prince, so she kisses him. He turns into a guy and stabs her to death.

Oh boy, we’re not off to a great start here. This story could have been told in a page or so and been an interesting twist on the old tale, but instead the author drew it out over three pages by choosing the absolute most pretentious choice of words for every damn sentence. The guy doesn’t stab the woman, his “knife describes a Gothic arc.” She doesn’t shout or whisper or ask what’s going on, she “expels a querrelous trauma.” It’s not snowing on her face, “trifles of ice as beautiful as they were capricious tickled her exposed cheeks, only to be turned into simulacra of tears as they were instantly metamorphosed by the bundled furnace of her body.”

Yes, really.

The sheer purpleness of this prose might be excused for a deliberately lofty and overwrought tale, but it absolutely does not fit a story about a girl getting shanked by a frog on the street. If the contrast between what’s happening and how it’s presented is supposed to seem absolutely ridiculous, then it’s a success. This reads more like a writing exercise for seeing how unbearably melodramatic you can tell a simple story that the author went ahead and published anyway. I only read it last night as of the time of this particular bit of review, but I still have a headache.

“Divine Right” by Nancy Holder – A king grieving for his recently passed daughter and only heir tries to figure out how to keep his legacy from dying out and eventually decides on a way to choose a successor, sealing his decision by making a pact with God.

I really liked this one, partly for the great characterization of the king via his priorities. He’s not a bastion of righteousness or a tyrannical despot. He might be a pretty decent ruler, or he might not, depending on your priorities and the angle from which you view him. Mostly he’s written to be believable for his position and time period, pride and failings and all.

But what really sealed this story for me was the ironic bent of the plot that I can’t really discuss in any more depth without spoiling it except to say that it definitely fit with the tone and left an appropriate message. So let’s just give it a thumbs up and leave it at that.

“In the Name of the King” by Judith Tarr – If you know the story of Hatshepsut, an Egyptian queen who ruled as Pharaoh, then this is an extra interesting story. It follows both Hatshepsut and her lover in the afterlife and the legacy they’re leaving behind after their deaths, in which they take a surprisingly active interest for dead people.

If you know your history, though, you know where this is going, and it’s very touching as it gets there. It’s also character-centric in a way that makes its dead cast members seem very much alive. This one’s a good contender for my favorite story in the whole anthology.

“Please to See the King” by Debra Doyle and James D. Macdonald – A small glimpse of about one evening each into the lives of two seemingly unrelated, seemingly unimportant men against the backdrop of the battles being fought over a vague and distant rebellion against a vague and distant crown.

To say more would be to spoil the story, which is short, sweet, and interesting. It gives you just enough details, and no more, that you can piece together a much deeper story with room left for speculation about who certain characters really were and what exactly just happened. I’ve spent more time thinking about how the ending may be interpreted than it took me to read it, which is a good sign of nuance done right.

“The Name of a King” by Diana L. Paxson – This’n c’n rightf’ly b’ put in w’ th’ other st’ries I woul’n’t oth’rwise b’ther t’ mention ‘cept fer th’ o’erwrought dialectic style o’ nearly all o’ th’ dialogue, whut c’n git on yer nerves right quick-like whene’er any’ne op’ns their mouths. An’ while I’m ‘ere, th’ settin’ w’s rife wi’ plen’y o’ hints at deeper d’tails whut was ne’er sufficien’ly delved into or whut impact’d th’ actu’l plot much. Felt like part o’ a fant’sy series whut I was ‘spected t’ b’ f’miliar wit’ but wasn’t, an’ whut di’n’t give me ’nuff t’ git f’miliar wit’ just fr’m this st’ry.

Oth’rwise, t’w’sn’t t’ b’d, I s’pose. Bit borin’.

“Coda: Working Stiff” by Mike Resnick and Nicholas A. DiChario – This one was just fun. Again trying not to give away any twists or revelations, this one follows a journalist interviewing a bus driver who used to be a big, famous king back in his heyday but is now content (or so he says) with his obscure life of working a simple job in the day and drinking in his spartan home at night.

Who this ex-king really is probably isn’t who you think it’s gonna be at first, but the story does still technically, and cheekily, fit in with the premise of the book overall. It reminds me very much of something Neil Gaiman might have written, or maybe Terry Pratchett if he’d decided to tackle the kingly premise from a more modern and realistic approach.

There are still 14 stories left in here, many of which are also good reads, or at least decent. In fact, looking back through it again, the only real dud that stands out to me is “The Kiss.” The weakest of what’s left are either adaptations of stories that didn’t really do it for me (“The Tale of Lady Ashburn” by John Gregory Betancourt) or weird original works that weren’t really memorable in what they set out to do (“A Parker House Roll” by Dean Wesley Smith).

Overall, The Book of Kings is a fun and interesting romp through a number of royal worlds, themes, and tones. As such, anyone who gives it a look will probably have the same general sentiment I did at the end, with a few things to like and a few to point to as examples of what doesn’t work for them. Me, I got a bit of the inspiration I was looking for and a few memorable tales out of it, so I’ll forgive the warts.

So since I can’t review it with one blanket sentiment, let’s instead take a quick look at a handful of the 20 all-original stories inside. The following are the tales that most stood out to me during my reading, for better or worse.

“The Kiss” by Alan Dean Foster – A woman walking through a snowy city finds a frog who says he’s a prince, so she kisses him. He turns into a guy and stabs her to death.

Oh boy, we’re not off to a great start here. This story could have been told in a page or so and been an interesting twist on the old tale, but instead the author drew it out over three pages by choosing the absolute most pretentious choice of words for every damn sentence. The guy doesn’t stab the woman, his “knife describes a Gothic arc.” She doesn’t shout or whisper or ask what’s going on, she “expels a querrelous trauma.” It’s not snowing on her face, “trifles of ice as beautiful as they were capricious tickled her exposed cheeks, only to be turned into simulacra of tears as they were instantly metamorphosed by the bundled furnace of her body.”

Yes, really.

The sheer purpleness of this prose might be excused for a deliberately lofty and overwrought tale, but it absolutely does not fit a story about a girl getting shanked by a frog on the street. If the contrast between what’s happening and how it’s presented is supposed to seem absolutely ridiculous, then it’s a success. This reads more like a writing exercise for seeing how unbearably melodramatic you can tell a simple story that the author went ahead and published anyway. I only read it last night as of the time of this particular bit of review, but I still have a headache.

“Divine Right” by Nancy Holder – A king grieving for his recently passed daughter and only heir tries to figure out how to keep his legacy from dying out and eventually decides on a way to choose a successor, sealing his decision by making a pact with God.

I really liked this one, partly for the great characterization of the king via his priorities. He’s not a bastion of righteousness or a tyrannical despot. He might be a pretty decent ruler, or he might not, depending on your priorities and the angle from which you view him. Mostly he’s written to be believable for his position and time period, pride and failings and all.

But what really sealed this story for me was the ironic bent of the plot that I can’t really discuss in any more depth without spoiling it except to say that it definitely fit with the tone and left an appropriate message. So let’s just give it a thumbs up and leave it at that.

“In the Name of the King” by Judith Tarr – If you know the story of Hatshepsut, an Egyptian queen who ruled as Pharaoh, then this is an extra interesting story. It follows both Hatshepsut and her lover in the afterlife and the legacy they’re leaving behind after their deaths, in which they take a surprisingly active interest for dead people.

If you know your history, though, you know where this is going, and it’s very touching as it gets there. It’s also character-centric in a way that makes its dead cast members seem very much alive. This one’s a good contender for my favorite story in the whole anthology.

“Please to See the King” by Debra Doyle and James D. Macdonald – A small glimpse of about one evening each into the lives of two seemingly unrelated, seemingly unimportant men against the backdrop of the battles being fought over a vague and distant rebellion against a vague and distant crown.

To say more would be to spoil the story, which is short, sweet, and interesting. It gives you just enough details, and no more, that you can piece together a much deeper story with room left for speculation about who certain characters really were and what exactly just happened. I’ve spent more time thinking about how the ending may be interpreted than it took me to read it, which is a good sign of nuance done right.

“The Name of a King” by Diana L. Paxson – This’n c’n rightf’ly b’ put in w’ th’ other st’ries I woul’n’t oth’rwise b’ther t’ mention ‘cept fer th’ o’erwrought dialectic style o’ nearly all o’ th’ dialogue, whut c’n git on yer nerves right quick-like whene’er any’ne op’ns their mouths. An’ while I’m ‘ere, th’ settin’ w’s rife wi’ plen’y o’ hints at deeper d’tails whut was ne’er sufficien’ly delved into or whut impact’d th’ actu’l plot much. Felt like part o’ a fant’sy series whut I was ‘spected t’ b’ f’miliar wit’ but wasn’t, an’ whut di’n’t give me ’nuff t’ git f’miliar wit’ just fr’m this st’ry.

Oth’rwise, t’w’sn’t t’ b’d, I s’pose. Bit borin’.

“Coda: Working Stiff” by Mike Resnick and Nicholas A. DiChario – This one was just fun. Again trying not to give away any twists or revelations, this one follows a journalist interviewing a bus driver who used to be a big, famous king back in his heyday but is now content (or so he says) with his obscure life of working a simple job in the day and drinking in his spartan home at night.

Who this ex-king really is probably isn’t who you think it’s gonna be at first, but the story does still technically, and cheekily, fit in with the premise of the book overall. It reminds me very much of something Neil Gaiman might have written, or maybe Terry Pratchett if he’d decided to tackle the kingly premise from a more modern and realistic approach.

There are still 14 stories left in here, many of which are also good reads, or at least decent. In fact, looking back through it again, the only real dud that stands out to me is “The Kiss.” The weakest of what’s left are either adaptations of stories that didn’t really do it for me (“The Tale of Lady Ashburn” by John Gregory Betancourt) or weird original works that weren’t really memorable in what they set out to do (“A Parker House Roll” by Dean Wesley Smith).

Overall, The Book of Kings is a fun and interesting romp through a number of royal worlds, themes, and tones. As such, anyone who gives it a look will probably have the same general sentiment I did at the end, with a few things to like and a few to point to as examples of what doesn’t work for them. Me, I got a bit of the inspiration I was looking for and a few memorable tales out of it, so I’ll forgive the warts.

Paul Chesworth (3 KP) created a post

Feb 20, 2018

Cody Cook (8 KP) rated Writings Of Thomas Paine Volume 4 (1794 1796); The Age Of Reason in Books

Jun 29, 2018

Thomas Paine was a political theorist who was perhaps best known for his support for the American Revolution in his pamphlet Common Sense. In what might be his second best known work, The Age of Reason, Paine argued in favor of deism and against the Christian religion and its conception of God. By deism it is meant the belief in a creator God who does not violate the laws of nature by communicating through revelation or miracles The book was very successful and widely read partly due to the fact that it was written in a style which appealed to a popular audience and often implemented a sarcastic, derisive tone to make its points.

The book seems to have had three major objectives: the support of deism, the ridicule of what Paine found loathsome in Christian theology, and the demonstration of how poor an example the Bible is as a reflection of God.

In a sense, Paine's arguments against Christian theology and scripture were meant to prop up his deistic philosophy. Paine hoped that in demonizing Christianity while giving evidences for God, he would somehow have made the case for deism. But this is not so. If Christianity is false, but God exists nonetheless, we are not left only with deism. There are an infinite number of possibilities for us to examine regarding the nature of God, and far too many left over once we have eliminated the obviously false ones. In favor of deism Paine has only one argument—his dislike of supernatural revelation, which is to say that deism appeals to his culturally derived preferences. In any case, Paine's thinking on the matter seemed to be thus: if supernatural revelation could be shown to be inadequate and the development of complex theology shown to be an error, one could still salvage a belief in God as Creator, but not as an interloper in human affairs who required mediators.

That being said, in his support of deism, Paine makes some arguments to demonstrate the reasonableness in belief in, if not the logical necessity of the existence of, God which could be equally used by Christians.

For instance, just as the apostle Paul argued in his epistle to the Romans that, "what can be known about God is plain to [even pagans], because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made" (Romans 1:19-20, ESV), so also Paine can say that, "the Creation speaketh an universal language [which points to the existence of God], independently of human speech or human language, multiplied and various as they be."

The key point on which Paine differs from Paul on this issue is in his optimism about man's ability to reason to God without His assisting from the outside. Whereas Paul sees the plainness of God from natural revelation as an argument against the inherent goodness of a species which can read the record of nature and nevertheless rejects its Source's obvious existence, Paine thinks that nature and reason can and do lead us directly to the knowledge of God's existence apart from any gracious overtures or direct revelation.

On the witness of nature, Paine claims, and is quite correct, that, "THE WORD OF GOD IS THE CREATION WE BEHOLD: And it is in this word, which no human invention can counterfeit or alter, that God speaketh universally to man." What is not plainly clear, however, is that man is free enough from the noetic effects of sin to reach such an obvious conclusion on his own. Indeed, the attempts of mankind to create a religion which represents the truth have invariably landed them at paganism. By paganism I mean a system of belief based, as Yehezkel Kaufmann and John N. Oswalt have shown, on continuity.iv In polytheism, even the supernatural is not really supernatural, but is perhaps in some way above humans while not being altogether distinct from us. What happens to the gods is merely what happens to human beings and the natural world writ large, which is why the gods are, like us, victims of fate, and why pagan fertility rituals have attempted to influence nature by influencing the gods which represent it in accordance with the deeper magic of the eternal universe we all inhabit.

When mankind has looked at nature without the benefit of supernatural revelation, he has not been consciously aware of a Being outside of nature which is necessarily responsible for it. His reasoning to metaphysics is based entirely on his own naturalistic categories derived from his own experience. According to Moses, it took God revealing Himself to the Hebrews for anyone to understand what Paine thinks anyone can plainly see.

The goal of deism is to hold onto what the western mind, which values extreme independence of thought, views as attractive in theism while casting aside what it finds distasteful. But as C.S. Lewis remarked, Aslan is not a tame lion. If a sovereign God exists, He cannot be limited by your desires of what you'd like Him to be. For this reason, the deism of men like Paine served as a cultural stepping stone toward the atheism of later intellectuals.

For Paine, as for other deists and atheists like him, it is not that Christianity has been subjected to reason and found wanting, but that it has been subjected to his own private and culturally-determined tastes and preferences and has failed to satisfy. This is the flipside of the anti-religious claim that those who believe in a given religion only do so because of their cultural conditioning: the anti-religionist is also conditioned in a similar way. Of course, how one comes to believe a certain thing has no bearing on whether that thing is true in itself, and this is true whether Christianity, atheism, or any other view is correct. But it must be stated that the deist or atheist is not immune from the epistemic difficulties which he so condescendingly heaps on theists.

One of the befuddling ironies of Paine's work is that around the time he was writing about the revealed religions as, “no other than human inventions set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit," the French were turning churches into “temples of reason” and murdering thousands at the guillotine (an instrument of execution now most strongly identified with France's godless reign of terror). Paine, who nearly lost his own life during the French Revolution, saw the danger of this atheism and hoped to stay its progress, despite the risk to his own life in attempting to do so.

What is odd is that Paine managed to blame this violent atheism upon the Christian faith! Obfuscated Paine:

"The Idea, always dangerous to Society as it is derogatory to the Almighty, — that priests could forgive sins, — though it seemed to exist no longer, had blunted the feelings of humanity, and callously prepared men for the commission of all crimes. The intolerant spirit of church persecution had transferred itself into politics; the tribunals, stiled Revolutionary, supplied the place of an Inquisition; and the Guillotine of the Stake. I saw many of my most intimate friends destroyed; others daily carried to prison; and I had reason to believe, and had also intimations given me, that the same danger was approaching myself."

That Robespierre's deism finally managed to supplant the revolutionary state's atheism and that peace, love, and understanding did not then spread throughout the land undermines Paine's claims. Paine felt that the revolution in politics, especially as represented in America, would necessarily lead to a revolution in religion, and that this religious revolution would result in wide acceptance of deism. The common link between these two revolutions was the idea that the individual man was sovereign and could determine for himself what was right and wrong based on his autonomous reason. What Paine was too myopic to see was that in France's violence and atheism was found the logical consequence of his individualistic philosophy. In summary, it is not Christianity which is dangerous, but the spirit of autonomy which leads inevitably into authoritarianism by way of human desire.

As should be clear by now, Paine failed to understand that human beings have a strong tendency to set impartial reason aside and to simply evaluate reality based on their desires and psychological states. This is no more obvious than in his own ideas as expressed in The Age of Reason. Like Paine's tendency to designate every book in the Old Testament which he likes as having been written originally by a gentile and translated into Hebrew, so many of his criticisms of Christian theology are far more a reflection upon himself than of revealed Christianity. One has only to look at Paine's description of Jesus Christ as a “virtuous reformer and revolutionist” to marvel that Paine was so poor at introspection so as to not understand that he was describing himself.

There is much more that could be said about this work, but in the interest of being somewhat concise, I'll end my comments here. If you found this analysis to be useful, be sure to check out my profile and look for my work discussing Paine and other anti-Christian writers coming soon.

The book seems to have had three major objectives: the support of deism, the ridicule of what Paine found loathsome in Christian theology, and the demonstration of how poor an example the Bible is as a reflection of God.

In a sense, Paine's arguments against Christian theology and scripture were meant to prop up his deistic philosophy. Paine hoped that in demonizing Christianity while giving evidences for God, he would somehow have made the case for deism. But this is not so. If Christianity is false, but God exists nonetheless, we are not left only with deism. There are an infinite number of possibilities for us to examine regarding the nature of God, and far too many left over once we have eliminated the obviously false ones. In favor of deism Paine has only one argument—his dislike of supernatural revelation, which is to say that deism appeals to his culturally derived preferences. In any case, Paine's thinking on the matter seemed to be thus: if supernatural revelation could be shown to be inadequate and the development of complex theology shown to be an error, one could still salvage a belief in God as Creator, but not as an interloper in human affairs who required mediators.

That being said, in his support of deism, Paine makes some arguments to demonstrate the reasonableness in belief in, if not the logical necessity of the existence of, God which could be equally used by Christians.

For instance, just as the apostle Paul argued in his epistle to the Romans that, "what can be known about God is plain to [even pagans], because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made" (Romans 1:19-20, ESV), so also Paine can say that, "the Creation speaketh an universal language [which points to the existence of God], independently of human speech or human language, multiplied and various as they be."

The key point on which Paine differs from Paul on this issue is in his optimism about man's ability to reason to God without His assisting from the outside. Whereas Paul sees the plainness of God from natural revelation as an argument against the inherent goodness of a species which can read the record of nature and nevertheless rejects its Source's obvious existence, Paine thinks that nature and reason can and do lead us directly to the knowledge of God's existence apart from any gracious overtures or direct revelation.

On the witness of nature, Paine claims, and is quite correct, that, "THE WORD OF GOD IS THE CREATION WE BEHOLD: And it is in this word, which no human invention can counterfeit or alter, that God speaketh universally to man." What is not plainly clear, however, is that man is free enough from the noetic effects of sin to reach such an obvious conclusion on his own. Indeed, the attempts of mankind to create a religion which represents the truth have invariably landed them at paganism. By paganism I mean a system of belief based, as Yehezkel Kaufmann and John N. Oswalt have shown, on continuity.iv In polytheism, even the supernatural is not really supernatural, but is perhaps in some way above humans while not being altogether distinct from us. What happens to the gods is merely what happens to human beings and the natural world writ large, which is why the gods are, like us, victims of fate, and why pagan fertility rituals have attempted to influence nature by influencing the gods which represent it in accordance with the deeper magic of the eternal universe we all inhabit.

When mankind has looked at nature without the benefit of supernatural revelation, he has not been consciously aware of a Being outside of nature which is necessarily responsible for it. His reasoning to metaphysics is based entirely on his own naturalistic categories derived from his own experience. According to Moses, it took God revealing Himself to the Hebrews for anyone to understand what Paine thinks anyone can plainly see.

The goal of deism is to hold onto what the western mind, which values extreme independence of thought, views as attractive in theism while casting aside what it finds distasteful. But as C.S. Lewis remarked, Aslan is not a tame lion. If a sovereign God exists, He cannot be limited by your desires of what you'd like Him to be. For this reason, the deism of men like Paine served as a cultural stepping stone toward the atheism of later intellectuals.

For Paine, as for other deists and atheists like him, it is not that Christianity has been subjected to reason and found wanting, but that it has been subjected to his own private and culturally-determined tastes and preferences and has failed to satisfy. This is the flipside of the anti-religious claim that those who believe in a given religion only do so because of their cultural conditioning: the anti-religionist is also conditioned in a similar way. Of course, how one comes to believe a certain thing has no bearing on whether that thing is true in itself, and this is true whether Christianity, atheism, or any other view is correct. But it must be stated that the deist or atheist is not immune from the epistemic difficulties which he so condescendingly heaps on theists.

One of the befuddling ironies of Paine's work is that around the time he was writing about the revealed religions as, “no other than human inventions set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit," the French were turning churches into “temples of reason” and murdering thousands at the guillotine (an instrument of execution now most strongly identified with France's godless reign of terror). Paine, who nearly lost his own life during the French Revolution, saw the danger of this atheism and hoped to stay its progress, despite the risk to his own life in attempting to do so.

What is odd is that Paine managed to blame this violent atheism upon the Christian faith! Obfuscated Paine:

"The Idea, always dangerous to Society as it is derogatory to the Almighty, — that priests could forgive sins, — though it seemed to exist no longer, had blunted the feelings of humanity, and callously prepared men for the commission of all crimes. The intolerant spirit of church persecution had transferred itself into politics; the tribunals, stiled Revolutionary, supplied the place of an Inquisition; and the Guillotine of the Stake. I saw many of my most intimate friends destroyed; others daily carried to prison; and I had reason to believe, and had also intimations given me, that the same danger was approaching myself."

That Robespierre's deism finally managed to supplant the revolutionary state's atheism and that peace, love, and understanding did not then spread throughout the land undermines Paine's claims. Paine felt that the revolution in politics, especially as represented in America, would necessarily lead to a revolution in religion, and that this religious revolution would result in wide acceptance of deism. The common link between these two revolutions was the idea that the individual man was sovereign and could determine for himself what was right and wrong based on his autonomous reason. What Paine was too myopic to see was that in France's violence and atheism was found the logical consequence of his individualistic philosophy. In summary, it is not Christianity which is dangerous, but the spirit of autonomy which leads inevitably into authoritarianism by way of human desire.

As should be clear by now, Paine failed to understand that human beings have a strong tendency to set impartial reason aside and to simply evaluate reality based on their desires and psychological states. This is no more obvious than in his own ideas as expressed in The Age of Reason. Like Paine's tendency to designate every book in the Old Testament which he likes as having been written originally by a gentile and translated into Hebrew, so many of his criticisms of Christian theology are far more a reflection upon himself than of revealed Christianity. One has only to look at Paine's description of Jesus Christ as a “virtuous reformer and revolutionist” to marvel that Paine was so poor at introspection so as to not understand that he was describing himself.

There is much more that could be said about this work, but in the interest of being somewhat concise, I'll end my comments here. If you found this analysis to be useful, be sure to check out my profile and look for my work discussing Paine and other anti-Christian writers coming soon.

Cyn Armistead (14 KP) rated Carniepunk in Books

Mar 1, 2018

As soon as I read about this collection on Kevin Hearne's Facebook, I knew I would be buying it. I don't care for carnivals at all, and every story will be related to one in some way - but there was just no way I was going to miss an Atticus and Oberon story! I even pre-ordered the book on Amazon, the first time I've ever done that. It was SO hard not to skip right ahead and read Hearne's contribution the moment the book was in my hot little hands, but I managed some discipline.

Rob Thurman's "Painted Love" opens the book. It is dark, but to be fair it isn't quite as dark as the only Thurman novel I've read, from the Cal Leandros series. I rather liked the twist. I adored the fiercely protective older sister, especially the way she is described. I'll rate this one at three.

I don't believe I've ever read anything by Delilah S. Dawson before, certainly not anything in the Blud universe, so I had no idea what to expect from "The Three Lives of Lydia." It was a far darker story than I would generally choose to read. I found the male love interest highly appealing. The portrayal of mental illness was horrific. I found it interesting that Dawson is an Atlantan as well as a fellow geeky mom, but I'm sure that I've never heard of her before. She does have a book coming out next year that looks promising, so I may give it a read. This one's a two.

Then there is the Iron Druid story! "The Demon Barker of Wheat Street" is set a few books back in the series' chronology (two weeks after "Two Ravens and One Crow"), so Granuaille isn't yet a full Druid. To make things even more interesting, Atticus accidentally offended the local elemental many years ago, so his magic doesn't work as well as usual in the area. The story isn't vital to the series, and knowledge of the series isn't necessary for enjoying it. Hearne's fans definitely won't want to miss it, though, and it could be used as a nice little taste of his style for new readers. Definitely a five.

I couldn't make it through "The Sweeter the Juice" by Mark Henry. Zombies are disgusting, but I was way squicked before the first walking dead even appeared on the scene. A one, just because there are no zeroes.

Jaye Wells is another new-to-me author, as far as I can remember at the moment. I didn't really like "The Werewife," to be honest. There was no joy anywhere in this story. There wasn't even a hint that perhaps the couple in the story had been happy together at one time. Both of them seemed pretty miserable, and I didn't like the way it ended. It didn't seem like there was any way to give them a happy ending, but that ending didn't feel "true." It gets a two, and that's only to set it apart from the previous story.

"The Cold Girl" by Rachel Caine is about an abusive teen relationship. Oh, and vampires. I'm not a Caine fan, but this story was better than some of her other work. Again, too dark for my tastes. If half stars were possible, it would have one. I'll be nice and round up to three.

The name Allison Pang sounds familiar, so maybe I've read something by her in the past. If I did, I'm certain that it wasn't set in the same world as "A Duet With Darkness," which says it is an Abby Sinclair story. I found the main character to be an annoying, immature twit, but I'm a sucker for fiction with musical influences. The music is well-done here. I don't know if I will read anything more by Ms. Pang or not - I suppose that depends on whether or not her other work has better characters and is also musical. This one gets a four.

I found "Recession of the Divine" by Hillary Jacques fascinating. The Greek inspiration was unusual. I didn't really buy the customers being quite so unquestioning of Ophelia's state, but it wasn't a major complaint overall. I was highly disappointed to find nothing but a credit in another anthology for her. But! Reading the author profiles at the end of the book pays off, because that's how I learned that she also writes as Regan Summers. Now her works published under that name are on my to-read shelf. Another five.

Jennifer Estep's "Parlor Tricks" was actually released free on Amazon a little while back to promote Carniepunk, so it was the first story I read. I enjoy the Elemental Assassin series in general, and this story is no exception. Again, knowledge of the series is not required to understand the story, and the story is not vital to the series. It is a nice little sample, though, and I enjoyed seeing Gin and Bria having a sisterly outing. I'm probably biased, but it gets a five.

I liked Kelly Meding's "Freak House" a lot, and her name sounded familiar, but the story was set in the "Strays" universe, which I was certain I had never heard of before. I actually stirred myself to look her up, and learned that I've had one of her books on my to-read list for ages, and Strays is a new series she's just starting. Djinn, werewolves, vampires, pixies, harpies, leprechauns, skinwalkers, and more, some "out" to humans, some living hidden - what's not to love? This one gets a four.

Nicole Peeler us yet another author who sounded vaguely familiar to me, and yep, there is one of her books on my to-read list (yes, it is massive, why do you ask?). It is, in fact, the first of the Jane True books, and "The Inside Man" is set in that world. Peeler's writing style dies not flow for me, but I liked Capitola Jones and her friends Shar and Moo. As clowns are indisputably evil, I had little to complain about in the story. It gets a three.

Succubus (former?) Jezzie is the main character in Jackie Kessler's story "A Chance in Hell." Obviously, the story is set her Hell on Earth series. I had to look that up, though, because while I know you're shocked, her name did not ring any bells for me. I don't actually have ALL the urban fantasy books on my to-read or read lists! The piece opens with a confusing remark about a demon eating Jezebel's face, when that definitely is not the anatomy in question. If that's a common euphemism, it is wholly new to me. Within the next couple of pages there are multiple references to the fact that she has fallen in love with a human since becoming mortal, but absolutely no explanation of how she would reconcile sex with an incubus with her human love. As much as I would prefer that it were not the case, the default assumption in our society is that people are monogamous. Therefore, when there is a deviation from that norm, the reader expects - something. Is it supposed to demonstrate that the fictional society is different? Is the character in an explicitly non-monogamous relationship? Is her love unrequited? Is the guy dead? Do demons not count? Is she just a skanky ho? Then this great love isn't mentioned again for the rest of the story, so none of the questions raised are answered. Oh. There is, in fact, a plot here, but I was so annoyed by that stuff that I almost failed to notice it. Demonic circus, yo. The whole demon thing reminds me too much of another series I've read in the past. I can't even remember the author's name, much less the title, right now, but Kessler's work feels derivative. She gets a two.

Next up is Kelly Gay - Hey look! Another author whose name I don't recognize! - with "Hell's Menagerie," a Charlie Madigan short story. Okay, this series is set in an alternate Atlanta. As an Atlanta girl, that certainly gets my attention. And Charlie is a single mother. I don't recall any other single mothers in the UF world right off. (Kate Daniels doesn't quite count, because she adopted her daughter as a teen. Although it is interesting to note that Kate is also Atlanta-based.) I was ready to like this one, based solely on what I knew of the series. Then there was a grammatical error on the second page of the story that set my teeth on edge, one which could not be chalked up to a character's voice. Add in the fact that we get a fast, "and also, Jim" style introduction to Charlie (who isn't even present in the story!), Rex, and Emma in less than two pages, and I am officially annoyed. It isn't an old matinee movie, so surely that information could have been worked in a little more naturally? Emma won me over. Mostly. There's some, "Not another super-gifted kid," reaction, but I guess if the mother is supposed to be all that it's to be expected that the daughter might be special, too. Hmm. A three.

The last piece is Seaman McGuire's "Daughter of the Midway, the Mermaid, and the Open, Lonely, Sea." Is that title a mouthful, or what? It has the feel of a Toby Daye story, although it isn't subtitled as such, and there are no fae so maybe it isn't in that universe at all. As there are other stories in the book that are set in the same world as their author's series, yet not marked in any way, lack of a subtitle can't be taken as a negative indicator, though. In any case, the story is poignant, which I've come to expect from McGuire. I didn't really like it, but I didn't dislike it, either. I couldn't "feel" Ada in any true sense. I have the same problem with Toby. A three at best.

Overall, the book was decent. The ratings only average out to 3.21, but I'm very glad to have read the stories by Hearne and Estep. Discovering Jacques/Summers was absolutely worthwhile. I really hate that I read as much of Henry's story as I did. If I could delete that from my memory, it would probably raise the rating for everything else.

Rob Thurman's "Painted Love" opens the book. It is dark, but to be fair it isn't quite as dark as the only Thurman novel I've read, from the Cal Leandros series. I rather liked the twist. I adored the fiercely protective older sister, especially the way she is described. I'll rate this one at three.

I don't believe I've ever read anything by Delilah S. Dawson before, certainly not anything in the Blud universe, so I had no idea what to expect from "The Three Lives of Lydia." It was a far darker story than I would generally choose to read. I found the male love interest highly appealing. The portrayal of mental illness was horrific. I found it interesting that Dawson is an Atlantan as well as a fellow geeky mom, but I'm sure that I've never heard of her before. She does have a book coming out next year that looks promising, so I may give it a read. This one's a two.

Then there is the Iron Druid story! "The Demon Barker of Wheat Street" is set a few books back in the series' chronology (two weeks after "Two Ravens and One Crow"), so Granuaille isn't yet a full Druid. To make things even more interesting, Atticus accidentally offended the local elemental many years ago, so his magic doesn't work as well as usual in the area. The story isn't vital to the series, and knowledge of the series isn't necessary for enjoying it. Hearne's fans definitely won't want to miss it, though, and it could be used as a nice little taste of his style for new readers. Definitely a five.

I couldn't make it through "The Sweeter the Juice" by Mark Henry. Zombies are disgusting, but I was way squicked before the first walking dead even appeared on the scene. A one, just because there are no zeroes.

Jaye Wells is another new-to-me author, as far as I can remember at the moment. I didn't really like "The Werewife," to be honest. There was no joy anywhere in this story. There wasn't even a hint that perhaps the couple in the story had been happy together at one time. Both of them seemed pretty miserable, and I didn't like the way it ended. It didn't seem like there was any way to give them a happy ending, but that ending didn't feel "true." It gets a two, and that's only to set it apart from the previous story.

"The Cold Girl" by Rachel Caine is about an abusive teen relationship. Oh, and vampires. I'm not a Caine fan, but this story was better than some of her other work. Again, too dark for my tastes. If half stars were possible, it would have one. I'll be nice and round up to three.

The name Allison Pang sounds familiar, so maybe I've read something by her in the past. If I did, I'm certain that it wasn't set in the same world as "A Duet With Darkness," which says it is an Abby Sinclair story. I found the main character to be an annoying, immature twit, but I'm a sucker for fiction with musical influences. The music is well-done here. I don't know if I will read anything more by Ms. Pang or not - I suppose that depends on whether or not her other work has better characters and is also musical. This one gets a four.

I found "Recession of the Divine" by Hillary Jacques fascinating. The Greek inspiration was unusual. I didn't really buy the customers being quite so unquestioning of Ophelia's state, but it wasn't a major complaint overall. I was highly disappointed to find nothing but a credit in another anthology for her. But! Reading the author profiles at the end of the book pays off, because that's how I learned that she also writes as Regan Summers. Now her works published under that name are on my to-read shelf. Another five.

Jennifer Estep's "Parlor Tricks" was actually released free on Amazon a little while back to promote Carniepunk, so it was the first story I read. I enjoy the Elemental Assassin series in general, and this story is no exception. Again, knowledge of the series is not required to understand the story, and the story is not vital to the series. It is a nice little sample, though, and I enjoyed seeing Gin and Bria having a sisterly outing. I'm probably biased, but it gets a five.

I liked Kelly Meding's "Freak House" a lot, and her name sounded familiar, but the story was set in the "Strays" universe, which I was certain I had never heard of before. I actually stirred myself to look her up, and learned that I've had one of her books on my to-read list for ages, and Strays is a new series she's just starting. Djinn, werewolves, vampires, pixies, harpies, leprechauns, skinwalkers, and more, some "out" to humans, some living hidden - what's not to love? This one gets a four.

Nicole Peeler us yet another author who sounded vaguely familiar to me, and yep, there is one of her books on my to-read list (yes, it is massive, why do you ask?). It is, in fact, the first of the Jane True books, and "The Inside Man" is set in that world. Peeler's writing style dies not flow for me, but I liked Capitola Jones and her friends Shar and Moo. As clowns are indisputably evil, I had little to complain about in the story. It gets a three.