The Third Tower: Journeys in Italy

David Pearson, Antal Szerb and Len Rix

Book

A typically brilliant, ironic and moving travelogue by one of the twentieth century's greatest...

An Uncommon Protector

Book

Overwhelmed by the responsibilities of running a ranch on her own, Laurel Tracey decides to hire a...

Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power

Book

From twice-Pulitzer-Prize-winning author Steve Coll comes Private Empire, winner of the FT/GOLDMAN...

Goldeneye: Where Bond Was Born: Ian Fleming's Jamaica

Book

The top 10 Sunday Times Bestseller. "Completely fascinating, authoritative and intriguing." (William...

Neil Hannon recommended The Enigma Variations by Edward Elgal in Music (curated)

The World of Charles and Ray Eames

Book

This is the first comprehensive book on the Eames' legacy in over a decade, revealing the rich...

Design

Swimming in the Dark

Book

Set in early 1980s Poland against the violent decline of communism, a tender and passionate story of...

Historical Fiction Literary Fiction Communist Poland

The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America

Book

Winner of the John Hope Franklin Prize A Moyers & Company Best Book of the Year “A brilliant work...

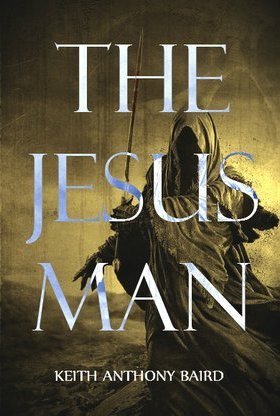

The Jesus Man

Book

It is 2037. Radicals in the Middle East have done the unthinkable. Low-yield nuclear weapons have...

ClareR (6074 KP) rated Hard By A Great Forest in Books

Mar 10, 2024

Saba, his brother and father escaped the conflict in post-Communist Georgia when he was a child, leaving behind their mother because they couldn’t afford the bribes. Saba’s father never recovers from having to leave her behind, and when things in Georgia start to settle down more, he returns there. However he goes missing, Saba’s brother goes to look for him and he goes missing too. So Saba goes to look for them both.

Saba’s head is full of the voices of his past, people who are no longer living and stories that his mother used to tell him. His brother leaves Saba a paper trail of clues, including the play that their father wrote, and parts of fairy stories and Shakespeare quotations from their childhood.

This is an emotional novel. There’s the constant feeling of being watched, danger is around every corner. The police are corrupt, and you don’t know if friends are really friends or working for the police.

Saba’s journey is both cathartic and dangerous. It takes him and his friend into the danger zone through a military blockade. It was so tense. Throughout, Saba has to deal with the trauma of his childhood and it’s impact on his adult life. He may have survived the war, but will he survive the trauma and the quest to find his father?

I loved this. I was rooting for Saba throughout, and I feel that I learnt a lot about what has happened in Georgia (considering I knew nothing beforehand). It’s wonderful book.